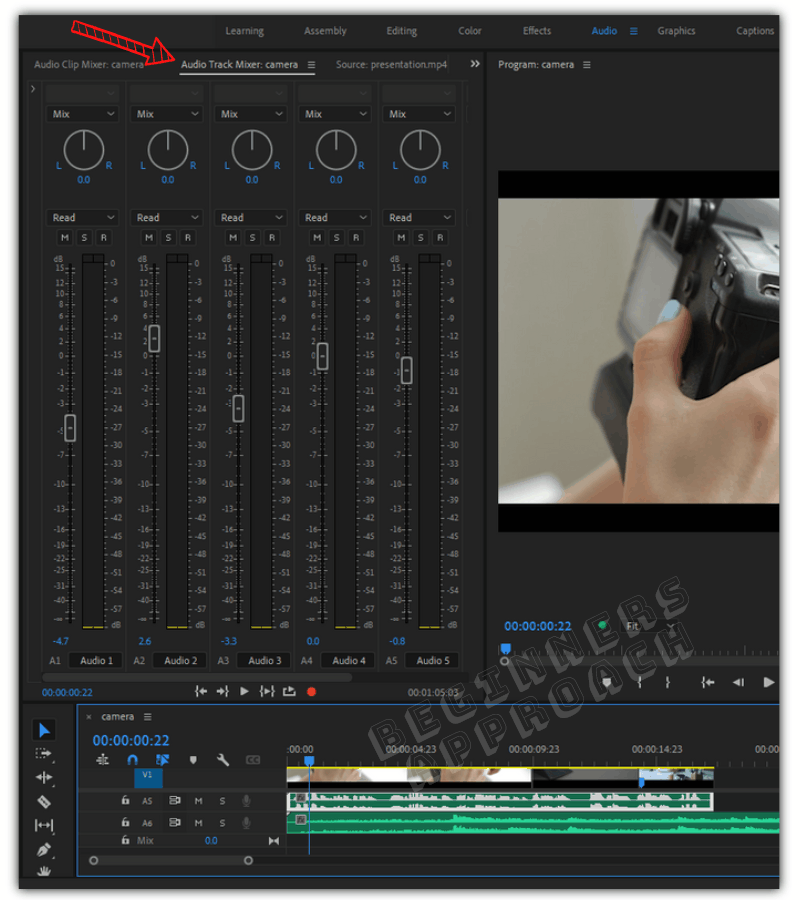

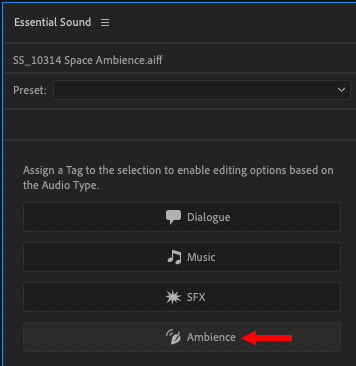

The visuals came out reasonably well (if a little dark, and I’m still kicking myself for one way-too-visible lav), but I was never satisfied with the audio. In this article, I’m going to try out auto-ducking on a case study video I did for a company called ActiveStandards a couple years back. For the types of videos I do, this feature would (I hoped) serve three purposes: improving the quality of my sound mixing using whatever algorithms Adobe had built into the applications to analyze and respond to the dynamics of the existing soundscape give me more facile tools for audio adjustments (as the new Essential Color panel had done for color correction) and automate the process of adjusting the background audio back up during breaks in the dialogue.

#Adobe premiere 7.0 sound ducking pro#

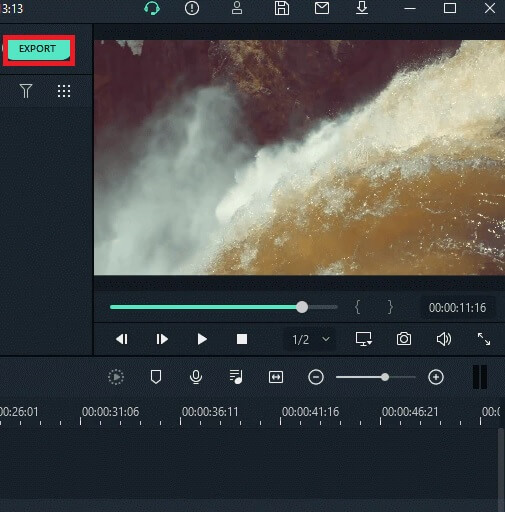

So when I heard that Adobe had introduced an Auto-Ducking feature into a new release of Premiere Pro CC earlier this year, I was eager to see and hear what it could do for me.

It's also a time-consuming and repetitive process when a video has multiple shifts between speakers or transitional breaks for titles or other clips. I know good sound ducking when I hear it, and I hear it all the time I just don’t have the feel for achieving it that I wish I did. Such has always been the case for me with circumstances that call for sound ducking, or adjusting a music track that’s been the primary (or only) component in a soundscape to a secondary, complementary role when the talent starts speaking. But on editing teams of one, sound mixing tends to be an aspect of postproduction that doesn’t play to a video editor’s strengths, and matching up sound to what you think you should be hearing can sometimes prove more challenging than correcting or grading a video to the look you want to see. In fact, it’s usually a lot simpler than sound design in the movies. Getting sound right in corporate and marketing video is typically a lot simpler than on “pocket symphony” rock records. Well-earned critical and fan hosannas aside, E Street Band guitarist Steve Van Zandt ultimately provided the clearest clinical assessment of what Springsteen achieved on that record: “He made something feel good that didn’t feel good at all when he was making it.” Even though the record they ended up with made Springsteen a star, and at least came close to realizing his epic ambitions, it took forever, and completing the album nearly killed everyone involved.

#Adobe premiere 7.0 sound ducking how to#

What’s more, by the time they set out to tackle these ambitious tracks, both had mastered the recording process to the degree that they knew how to bring the sounds in their heads, piece by piece, out into the world-and had the patience to do it-even if the singers, musicians, and engineers they enlisted to help them had little sense of what they were creating until all the pieces were in place.Ĭontrast those stories to the genesis of Bruce Springsteen’s roughly contemporaneous (to “Bohemian Rhapsody") Born to Run album, a tortured process through which neither Springsteen nor either of his producers had a clear idea of how to get the sound he wanted onto wax. If you’ve ever watched any of the mini-documentaries about the recording of Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” or the Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations,” you know that the primary composers of these dizzyingly complex songs, Freddie Mercury and Brian Wilson, respectively, essentially walked into the studio with nearly everything you hear on the record playing in their heads.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)